Today, if someone is diagnosed with HIV, he or she can choose among 41 drugs that can treat the disease. And there’s a good chance that with the right combination, given at the right time, the drugs can keep HIV levels so low that the person never gets sick.

That wasn’t always the case. It took seven years after HIV was first discovered before the first drug to fight it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In those first anxious years of the epidemic, millions were infected. Only a few thousand had died at that point, but public health officials were racing to keep that death rate from spiking — the inevitable result if people who tested positive weren’t treated with something.

As it turned out, their first weapon against HIV wasn’t a new compound scientists had to develop from scratch — it was one that was already on the shelf, albeit abandoned. AZT, or azidothymidine, was originally developed in the 1960s by a U.S. researcher as way to thwart cancer; the compound was supposed to insert itself into the DNA of a cancer cell and mess with its ability to replicate and produce more tumor cells. But it didn’t work when it was tested in mice and was put aside.

Two decades later, after AIDS emerged as new infectious disease, the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome, already known for its antiviral drugs, began a massive test of potential anti-HIV agents, hoping to find anything that might work against this new viral foe. Among the things tested was something called Compound S, a re-made version of the original AZT. When it was throw into a dish with animal cells infected with HIV, it seemed to block the virus’ activity.

The company sent samples to the FDA and the National Cancer Institute, where Dr. Samuel Broder, who headed the agency, realized the significance of the discovery. But simply having a compound that could work against HIV wasn’t enough. In order to make it available to the estimated millions who were infected, researchers had to be sure that it was safe and that it would indeed stop HIV in some way, even if it didn’t cure people of their infection. At the time, such tests, overseen by the FDA, took eight to 10 years.

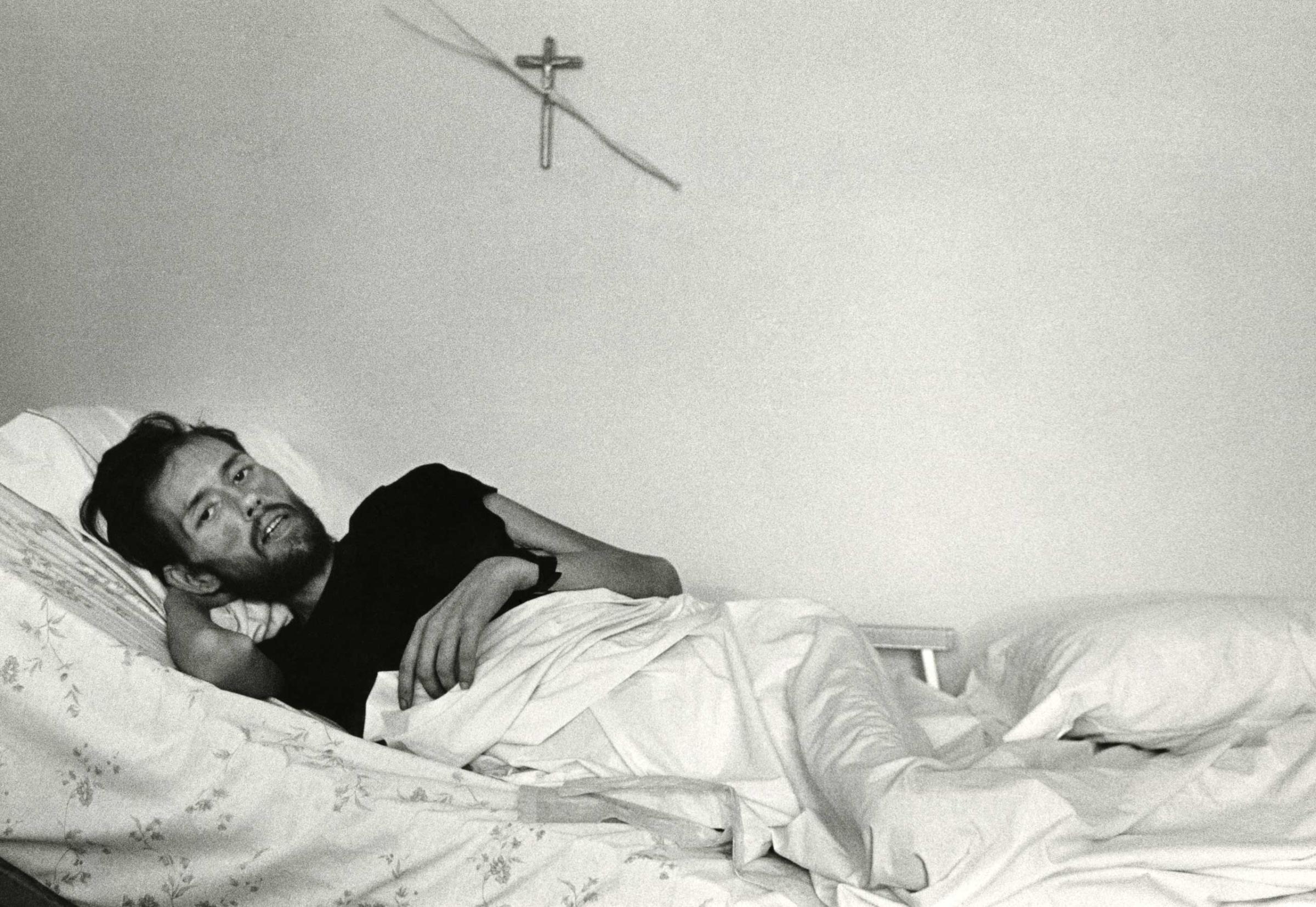

Patients couldn’t wait that long. Under enormous public pressure, the FDA’s review of AZT was fast tracked — some say at the expense of patients.

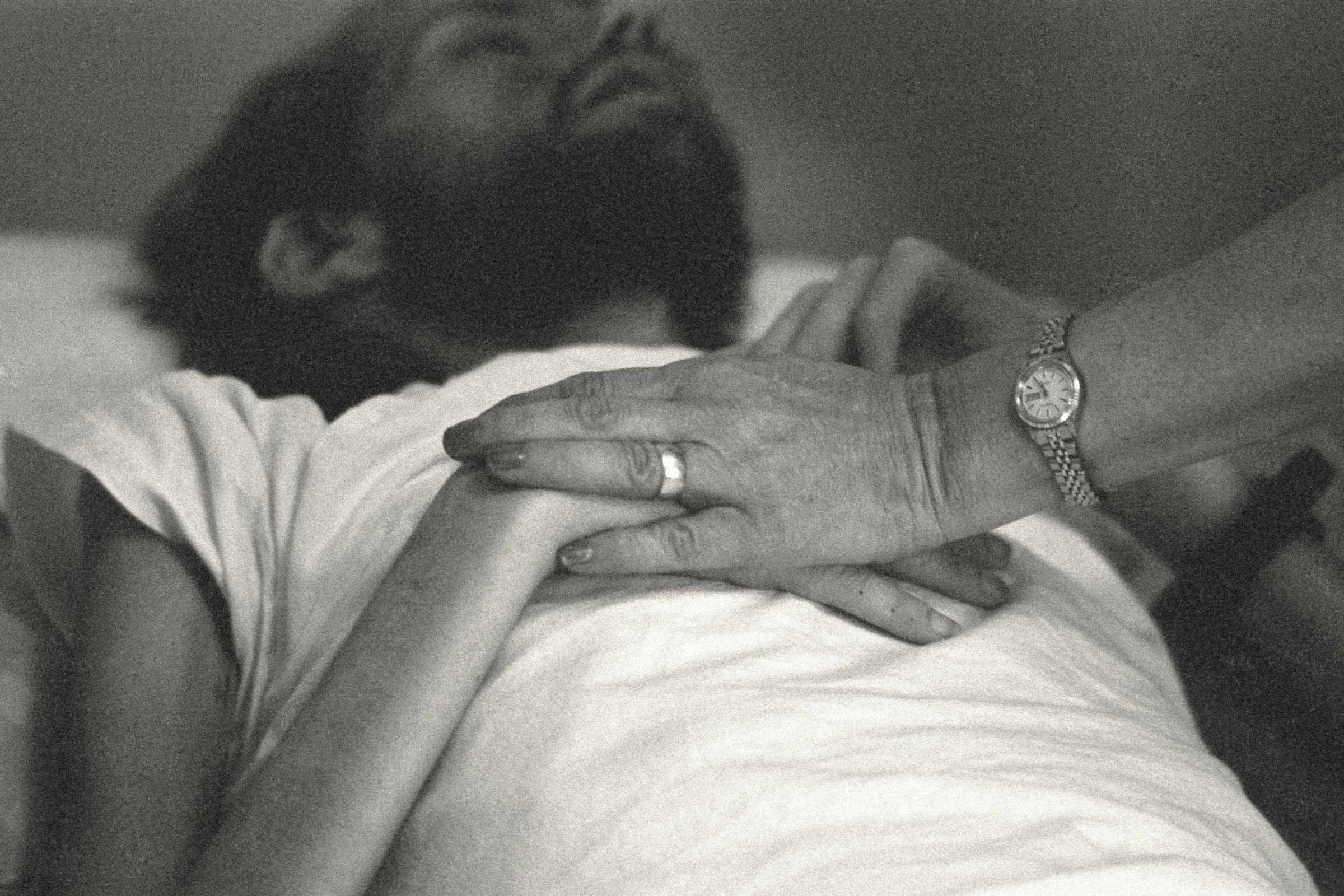

Scientists quickly injected AZT into patients. The first goal was to see whether it was safe — and, though it did cause side effects (including severe intestinal problems, damage to the immune system, nausea, vomiting and headaches) it was deemed relatively safe. But they also had to test the compound’s effectiveness. In order to do so, a controversial trial was launched with nearly 300 people who had been diagnosed with AIDS. The plan was to randomly assign the participants to take capsules of the agent or a sugar pill for six months. Neither the doctor nor the patient would know whether they were on the drug or not.

After 16 weeks, Burroughs Wellcome announced that they were stopping the trial because there was strong evidence that the compound appeared to be working. One group had only one death. Even in that short period, the other group had 19. The company reasoned that it wouldn’t be ethical to continue the trial and deprive one group of a potentially life-saving treatment.

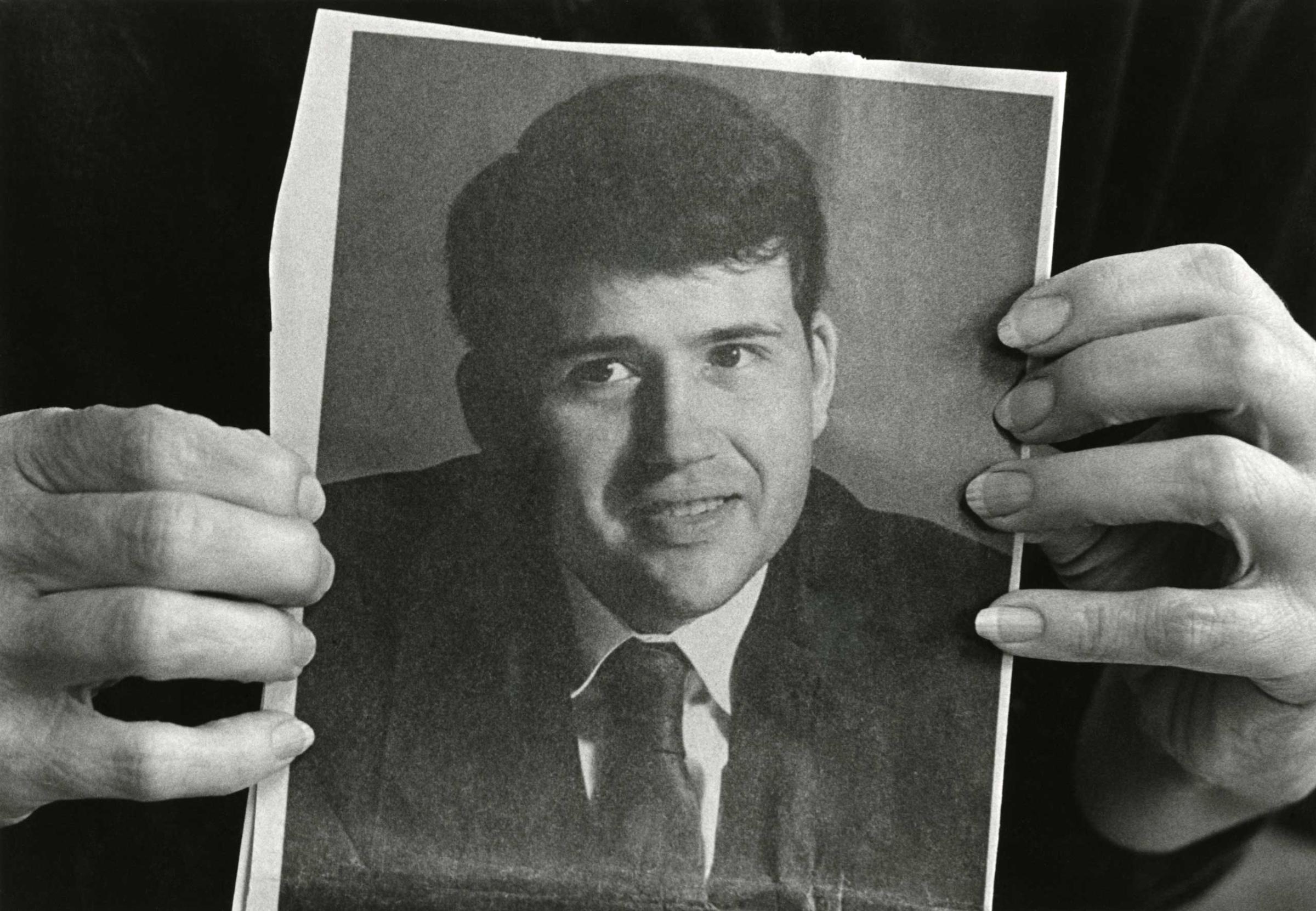

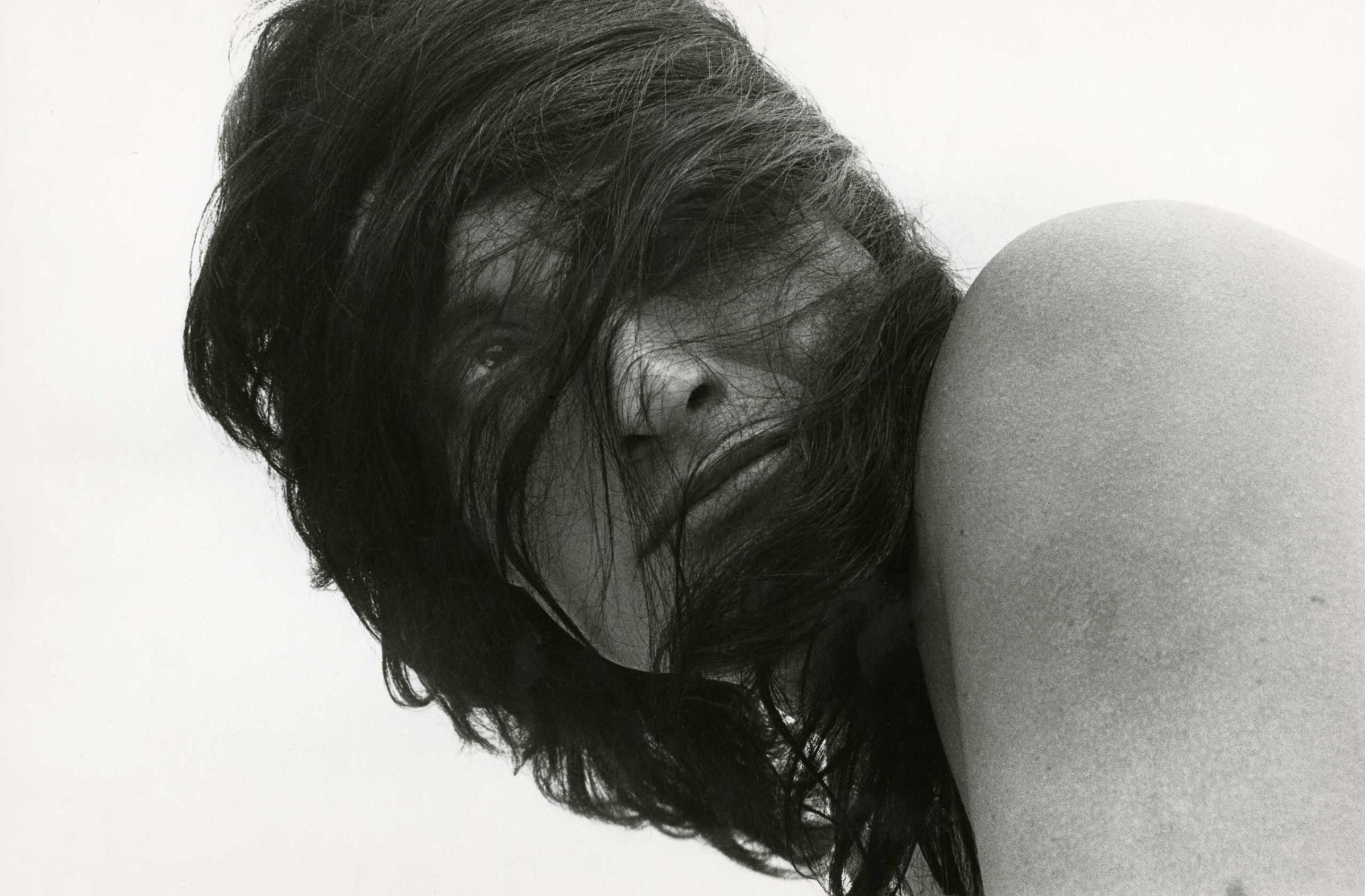

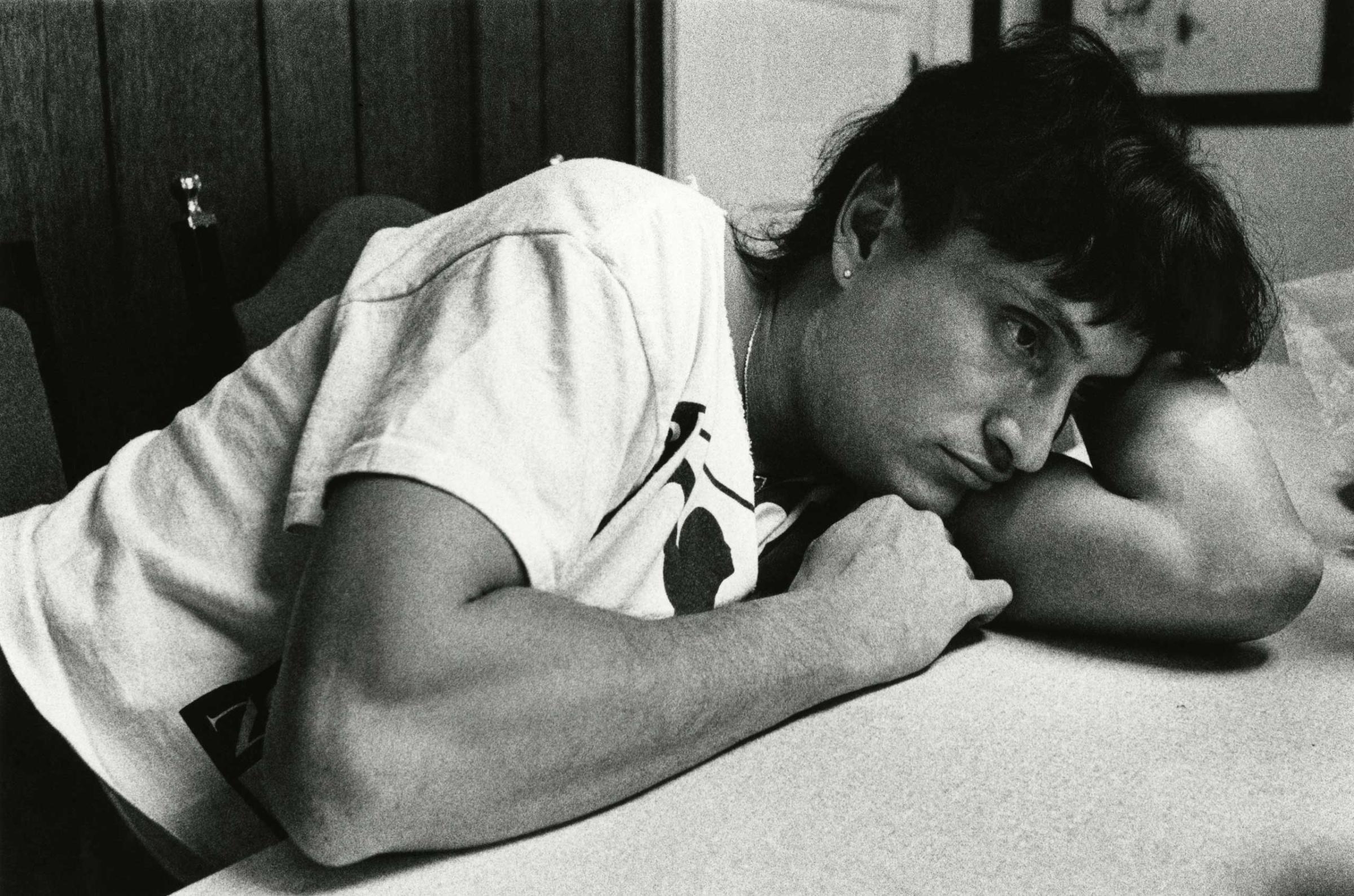

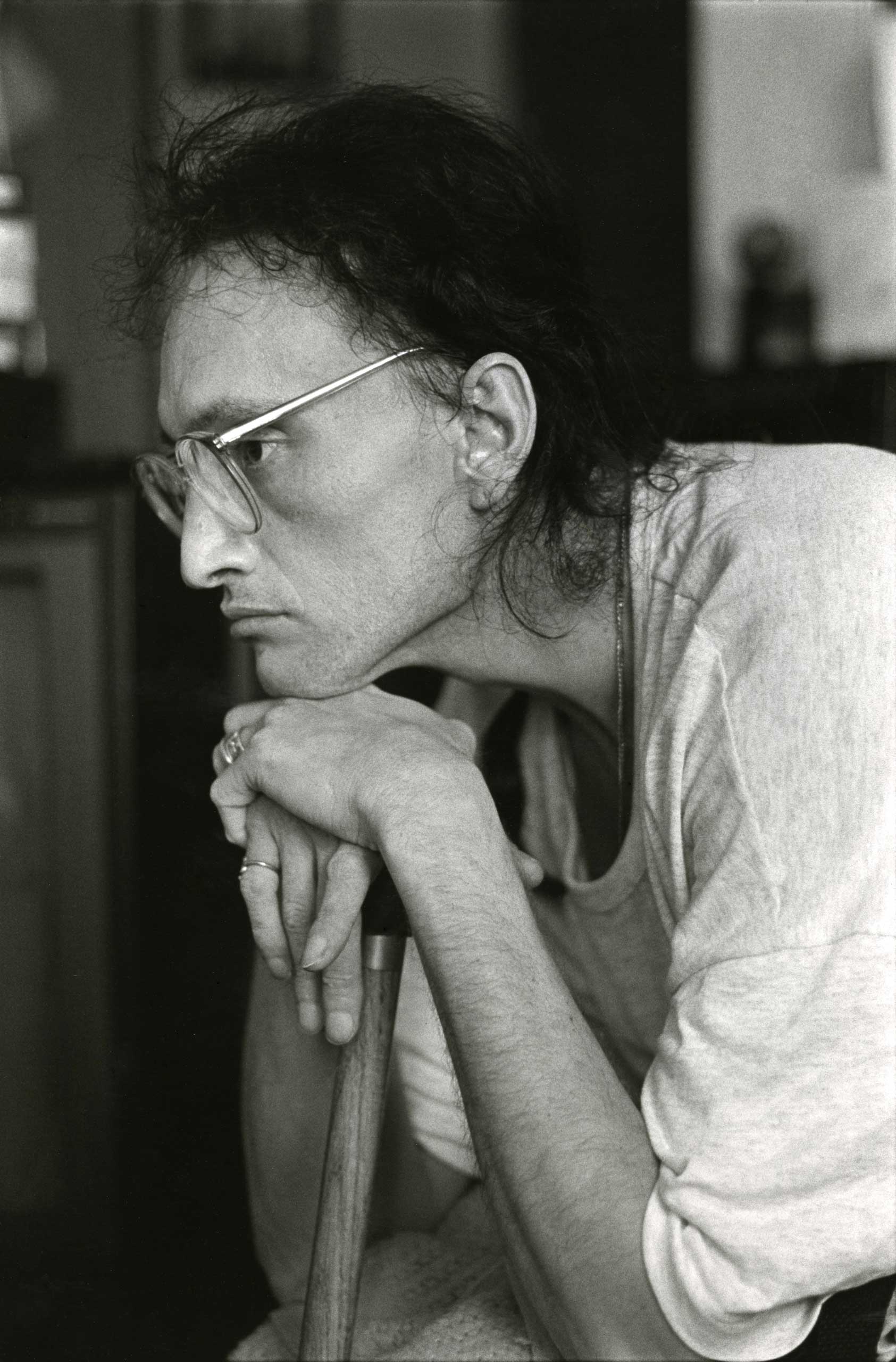

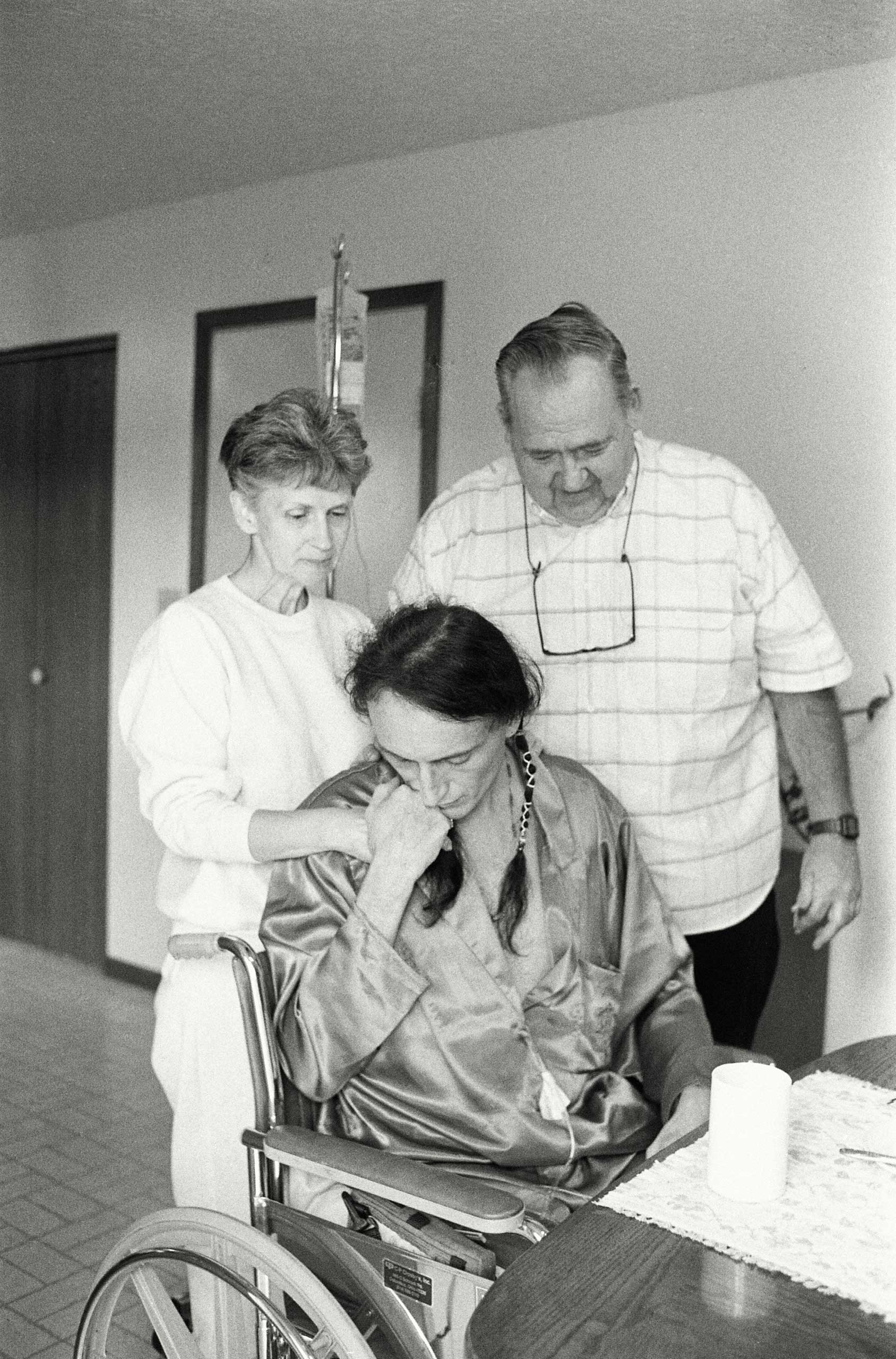

The Photo That Changed the Face of AIDS

Those results — and AZT — were heralded as a “breakthrough” and “the light at the end of the tunnel” by the company, and pushed the FDA approve the first AIDS medication on March 19, 1987, in a record 20 months.

But the study remains controversial. Reports surfaced soon after that the results may have been skewed since doctors weren’t provided with a standard way of treating the other problems associated with AIDS — pneumonia, diarrhea and other symptoms — which makes determining whether the AZT alone was responsible for the dramatic results nearly impossible. For example, some patients received blood transfusions to help their immune systems; introducing new, healthy blood and immune cells could have helped these patients battle the virus better. There were also stories of patients from the 12 centers where the study was conducted pooling their pills, to better the chances that they would get at least some of the drug rather than just placebos.

And there were still plenty of questions left unanswered about the drug when it was approved. How long did the apparent benefits last? Could people who weren’t sick yet still benefit? Did they benefit more than those further along in their disease?

Such uncertainty would not be acceptable with a traditional approval, but the urgent need to have something in hand to fight the growing epidemic forced FDA’s hand. The people in the trial were already pressuring the company and the FDA to simply release the drug — if there were something that worked against HIV, they said, then it was not ethical to withhold it.

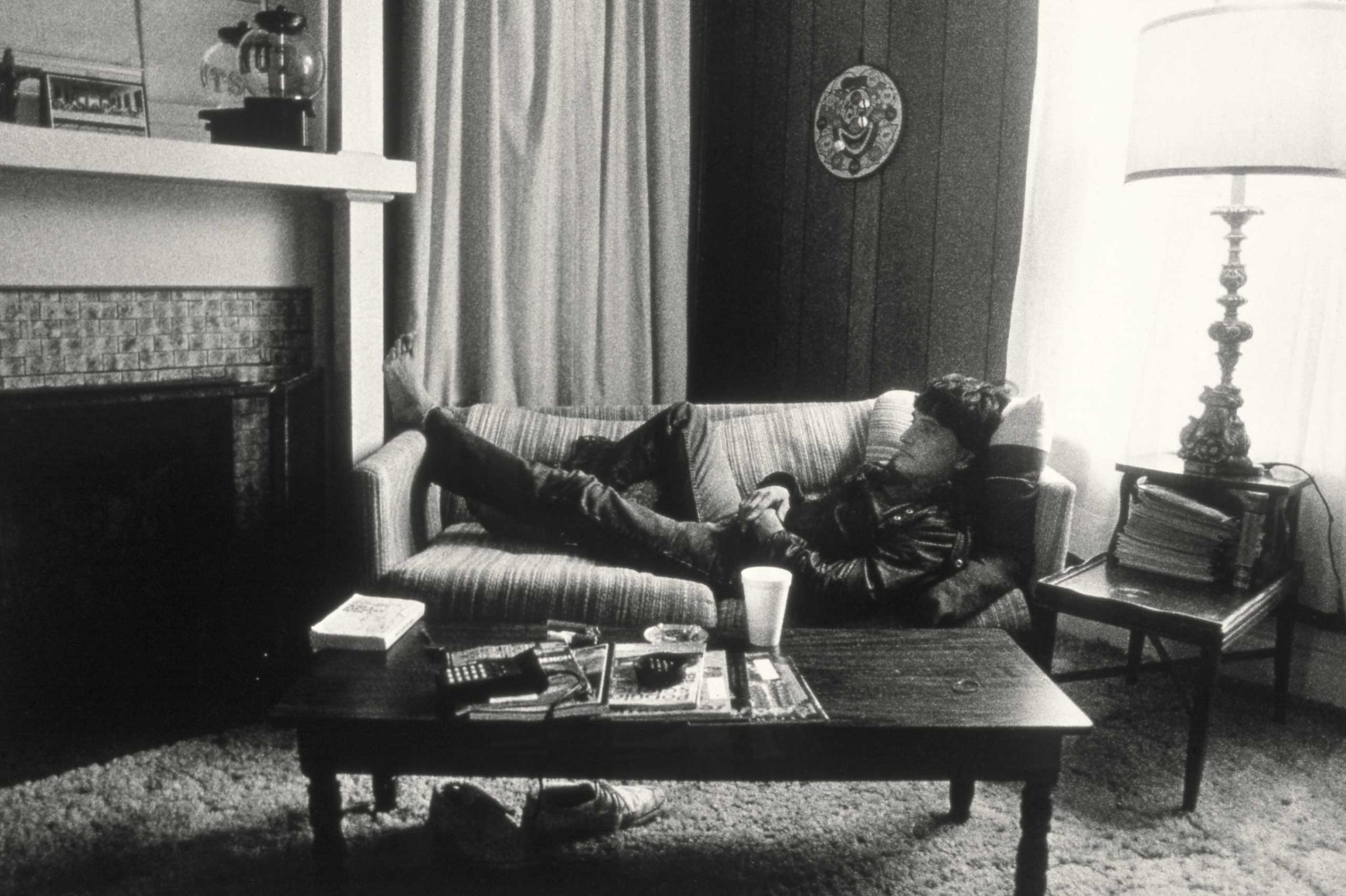

The drug’s approval remains controversial to this day, but in a world where treatment options are so far advanced it can be hard to imagine the sense of urgency and the social pressure permeating the medical community at the time. AIDS was an impending wave that was about to crash on the shores of an unsuspecting — and woefully unprepared — populace. Having at least one drug that worked, in however limited a way, was seen as progress.

But even after AZT’s approval, activists and public health officials raised concerns about the price of the drug. At about $8,000 a year (more than $17,000 in today’s dollars) — it was prohibitive to many uninsured patients and AIDS advocates accused Burroughs Wellcome of exploiting an already vulnerable patient population.

In the years since, it’s become clear that no single drug is the answer to fighting HIV. People taking AZT soon began showing rising virus levels — but the virus was no longer the same, having mutated to resist the drug. More drugs were needed, and AIDS advocates criticized the FDA for not moving quickly enough to approve additional medications. And side effects including heart problems, weight issues and more reminded people that anything designed to battle a virus like HIV was toxic.

Today, there are several classes of HIV drugs, each designed to block the virus at specific points in its life cycle. Used in combination, they have the best chance of keeping HIV at bay, lowering the virus’s ability to reproduce and infect, and ultimately, to cause death. These so-called antiretroviral drugs have made it possible for people diagnosed with HIV to live long and relatively healthy lives, as long they continue to take the medications.

And for most of these people, their therapy often still includes AZT.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com